A globe map is a map of most or all of the outer lining area of the World. World charts form a unique type of charts due to the problem of projector screen. Maps by necessity change the presentation of the planet's area. These disturbances reach extreme conditions in a globe map. The many ways of predicting the world indicate different technical and æsthetic goals for globe charts.[2]

World charts are also unique for the global information required to create them. A significant map around the globe could not be constructed before the Western Rebirth because less than half of the planet's coastlines, let alone its interior areas, were known to any lifestyle. New information of the planet's area has been gathering ever since and continues to this day.

Maps around the globe generally focus either on governmental functions or on actual functions. Political charts highlight territorial limitations and human settlement. Physical charts display geographical functions such as hills, ground type or land use. Geological charts display not only the outer lining area, but features of the actual rock, mistake lines, and subsurface components. Choropleth charts use color hue and strength to contrast variations between areas, such as market or economic research.

12 Charts That Modified the World

In July 2012, Mark McClendon, an professional at Search engines, declared that Search engines Charts and Search engines World were part of a far loftier desire than border out Apple company and Facebook or myspace in the map services industry. Search engines, McClendon had written in a short article, was involved in nothing less than a "never-ending desire for the best map."

"We’ve been building a extensive platform map of the whole globe—based on community and professional information, visuals from every stage (satellite, antenna and road level) and the combined knowledge of our an incredible number of customers," McClendon mentioned. By taping digital cameras to the supports of smart walkers, mobilizing customers to fact-check map information, and modelling the world in 3D, he included, Search engines was shifting one step nearer to mapmaking excellence.

It was the kind of technical triumphalism that Jerry Brotton would likely welcome with a knowing grin.

"All societies have always considered that the map they valorize is real and true and objective and clear," Brotton, a lecturer of Rebirth research at Master Jane School of London, uk, informed me. "All maps are always very subjective.... Even the present on the internet geospatial programs on all your cellular phones and pills, be they designed by Search engines or Apple company or whoever, are still at some stage very subjective maps."

There are, in other terms, no ideal maps—just maps that (more-or-less) completely catch our knowing around the world at unique minutes soon enough. In his new guide, A Record of the World in 12 Charts, Brotton well online catalogs the maps that tell us most about critical times in the past. I requested him simply to move me through the 12 maps he chosen (you can simply simply click each map below to expand it).

1. Cartography's Foundation: Ptolemy's Location (150 AD)

Humans have been drawing maps for thousands of years, but Claudius Ptolemy was the first to use mathematical and geometry to make a guide for how to map the globe using a rectangular shape and intersecting lines—one that resurfaced in 13th-century Byzantium and was used until the early Seventeenth millennium. The Alexandria-based Ancient pupil, who may never have attracted a map himself, described the permission and longitude of more than 8,000 locations in European nations, Asia, and African-american, predicting a north-oriented, Mediterranean-focused world that was losing the The nation's, Australasia, the southern part of African-american (you can see African-american cloths the end of the map and then mixing into Asia), the Far Eastern, the Hawaiian Sea, and most of the Ocean Sea. Ptolemy's Location was a "book with a 1,500-year heritage," Brotton says.

2. Social Exchange: Al-Idrisi's World Map (1154)

Al-Sharif al-Idrisi, a Islamic from Al-Andalus, visited to Sicily to perform for the Grettle Master Mark II, generating an Arabic-language geography information that attracted on Judaism, Ancient, Spiritual, and Islamic customs and involved two world maps: the small, round one above, and 70 local maps that could be padded together. Compared with east-oriented Spiritual world maps at time, al-Idrisi's map locations the southern part of at top in the custom of Islamic mapmakers, who regarded Paradise due the southern part of (Africa is the crescent-shaped where you live now at top, and the Arabian Peninsula is in the center). Compared with Ptolemy, al-Idrisi portrayed a circumnavigable Africa—blue sea encompasses the world. Eventually, the map is involved with comprising physical geography and mixing traditions—not arithmetic or trust. "There are no creatures on his maps," Brotton says.

3. Spiritual Faith: Hereford's Mappa Mundi (1300)

This map from England's Hereford Church symbolizes "what the world seemed like to ancient Christian believers," Brotton says. The planning concept in the east-oriented map 's time, not space, and particularly spiritual time; with Jesus emerging over the world, the audience moves emotionally from the Lawn of Eden at top down to the Support beams of Hercules near the Strait of Gibralter at platform (for a more specific trip, examine out this useful information to the map's landmarks). At the center is Jerusalem, noticeable with a crucifix, and to the right is African-american, whose shore is noticeable with repulsive creatures in the edges. "Once you get to the edges of what you know, those are risky locations," Brotton describes.

4. Imperial Politics: Kwon Kun's Kangnido Map (1402)

What's most stunning about this Japanese map, developed by a group of elegant astronomers led by Kwon Kun, is that north is at top. "It's unusual because the first map that looks identifiable to us as a European map is a map from South korea in 1402," Brotton notices. He chalks this up to power state policies in the area at time. "In South Oriental and China imperial philosophy, you look up northwards in regard to the emperor, and the emperor looks the southern part of to his topics," Brotton describes. European nations is a "tiny, savage speck" in the higher remaining, with a circumnavigable African-american below (it's uncertain whether the black covering in the center of African-american symbolizes a pond or a desert). The Arabian Peninsula is to Africa's right, and Indian is hardly noticeable. China suppliers is the enormous blob at the center of the map, with South korea, looking disproportionately large, to its right and the isle of Asia in the end right.

5. Territorial Exploration: Waldseemuller's Universalis Cosmographia (1507)

This perform by the In german cartographer Martin Waldseemuller is regarded the most expensive map on the world because, as Brotton notices, it is "America's beginning certificate"—a difference that persuaded the Collection of The legislature to buy it from a In german elegant prince for $10 thousand. It is the first map to identify the Hawaiian Sea and the individual area of "America," which Waldseemuller known as in regard of the then-still-living Amerigo Vespucci, who recognized the The nation's as a unique where you live now (Vespucci and Ptolemy appear at the top of the map). The map includes 12 woodcuts and features many of the newest findings by European adventurers (you get the sense that the woodcutter was requested at the last moment to make room for the Cpe of Good Hope). "This is when when the world goes hit, and all these findings are made over a few months frame," Brotton says.

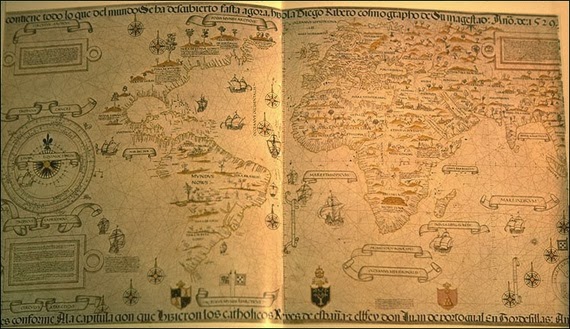

6. Politicized Geography: Ribeiro's World Map (1529)

The Colonial cartographer Diogo Ribeiro consisting this map amongst a nasty argument between Italy and This particular terminology over the Moluccas, an isle sequence in present-day Philippines and hub for the liven business (in 1494, the two nations had finalized a agreement splitting the recently found areas in two). After Ferdinand Magellan's adventure circumnavigated the world for initially in 1522, Ribeiro, operating for the Spanish terminology top, placed the "Spice Isles," inaccurately, just inside the Spanish terminology half of his apparently medical world maps. Ribeiro may have known that hawaii (which appear on the far-left and far-right factors of the map) actually belonged to This particular terminology, but he also realized who compensated the expenses. "This is the first great example of state policies adjusting geography," Brotton says.

7. Territorial Navigation: Mercator's World Map (1569)

Next to Ptolemy, Brotton says, Gerardus Mercator is the most significant determine in the reputation of mapmaking. The Flemish-German cartographer tried "on a smooth piece of document to imitate the curve of the planet's surface area," allowing "him to attract a directly range from, say, Lisbon to the European Coast of the Declares and sustain an effective range of keeping." Mercator, who was locked up by Catholic regulators for claimed Lutheran heresy, developed his map for European navigators. But Brotton believes it had a higher objective as well. "I think it’s a map about stoicism and transcendence," he says. "If you look at the world from several countless numbers kilometers up, at all these disputes in religious and governmental life, you are like bugs operating around." Mercator has been charged of Eurocentrism, since his projector screen, which is still sometimes used these days, progressively alters area as you go further the southern part of and north from the equator. Brotton dismisses this view, disagreeing that European nations isn't even at the center of the map.

8. Commercial Cartography: Blaeu's Atlas maior (1662)

Working for the Nederlander Eastern Indian Company, Joan Blaeu designed a wide atlas with thousands of baroque maps occupying a large number of webpages. "He's the last of a tradition: the single, amazing, magician-like mapmaker who says, 'I can amazingly show you the whole world,'" Brotton says. "By the delayed Seventeenth millennium, with combined stock organizations applying every area around the world, unknown groups of people are bashing information and generating maps." Blaeu's market-oriented maps weren't cutting-edge. But he did break with a mapmaking custom way returning to Ptolemy of putting the world at the center of the galaxy. At the top of the map, the sun is at the center of personifications of the five known planet's at the time—in a nod to Copernicus's concept of the galaxy, even as the world, separated into two hemispheres, continues to be at the center of the map, in deference to Ptolemy (Ptolemy is in the higher remaining, and Copernicus in the higher right). "Blau silently, very carefully says I think Copernicus is probably right," Brotton says.

9. Nationwide Mapping: Cassini's Map of Italy (1744)

Beginning under Louis XIV, four years of the Cassini family presided over the first make an effort to study and map every gauge of a country. The Cassinis used the technology of triangulation to make this nearly 200-sheet topographic map, which France revolutionaries nationalized in the delayed 1700s. This, Brotton says, "is the beginning of what we understand as contemporary nation-state applying ... whereas, before, mapmaking was in personal arms. Now, in the Search engines era, mapmaking is again going into personal arms."

10. Geopolitics: Mackinder's 'Geographical Rotate of History' (1904)

Don't let the modesty of this "little range drawing" deceive you, Brotton says: It "basically designed the whole idea that state policies is motivated at some stage by geographical problems." The British geographer and imperialist Halford Mackinder involved the illustrating in a document disagreeing that Russian federation and Main Asia constituted "the pivot of the state policies." Brotton considers this idea—that control of certain critical areas can convert into worldwide hegemony—has affected numbers which range from the Nazis to Henry Orwell to Gretchen Kissinger.

11. Geoactivism: Peters's Projection (1973)

In 1973, the left-wing In german historian Arno Peters revealed an substitute to Mercator's supposedly Eurocentric projection: a world map illustrating nations and major areas according to their actual surface area area—hence the smaller-than-expected north major areas, and African-american and South The america showing, in Brotton's terms, "like long, swollen split falls." The 'equal area' projector screen, which was nearly similar to an previously design by the Scottish clergyman Wayne Gall, was a hit with the media and contemporary NGOs. But experts suggested that any projector screen of a rounded surface area onto a aircraft surface area includes disturbances, and that Peters had elevated these by choosing serious statistical mistakes. "No map is any better or more intense than any other map," Brotton says. "It's just about what plan it chases."

The European Side enshrined the Peters Projection in popular lifestyle during an show in which the fake Organization of Cartographers for Social Equivalent rights lobbies the White House to make it compulsory for community educational institutions to educate Peters's map rather than Mercator's.

12. Exclusive Mapping: Search engines World (2005)

Google is at the leading advantage of enhancements in digital mapmaking, Brotton says. But he also notices that the company recognizes maps as an adjunct to search and marketing. "My query is what gets on maps, who will pay to get on maps now, and who can't pay and is therefore not on maps?" he requests. Long ago in Mercator's day, resource rule contains the projector screen the cartographer used and the information he fed into it. Now, Brotton notices, we don't know what resource rule Search engines and other on the internet applying programs are using. And this at some point when Search engines, which provides customers more than 20 petabytes of visuals, is dealing with far more content than a country can coordinate. "Companies can now generate maps in more details than, say, the U.K. Ordnance Survey, but without any peer-observation process," Brotton claims.

World charts are also unique for the global information required to create them. A significant map around the globe could not be constructed before the Western Rebirth because less than half of the planet's coastlines, let alone its interior areas, were known to any lifestyle. New information of the planet's area has been gathering ever since and continues to this day.

Maps around the globe generally focus either on governmental functions or on actual functions. Political charts highlight territorial limitations and human settlement. Physical charts display geographical functions such as hills, ground type or land use. Geological charts display not only the outer lining area, but features of the actual rock, mistake lines, and subsurface components. Choropleth charts use color hue and strength to contrast variations between areas, such as market or economic research.

12 Charts That Modified the World

In July 2012, Mark McClendon, an professional at Search engines, declared that Search engines Charts and Search engines World were part of a far loftier desire than border out Apple company and Facebook or myspace in the map services industry. Search engines, McClendon had written in a short article, was involved in nothing less than a "never-ending desire for the best map."

"We’ve been building a extensive platform map of the whole globe—based on community and professional information, visuals from every stage (satellite, antenna and road level) and the combined knowledge of our an incredible number of customers," McClendon mentioned. By taping digital cameras to the supports of smart walkers, mobilizing customers to fact-check map information, and modelling the world in 3D, he included, Search engines was shifting one step nearer to mapmaking excellence.

It was the kind of technical triumphalism that Jerry Brotton would likely welcome with a knowing grin.

"All societies have always considered that the map they valorize is real and true and objective and clear," Brotton, a lecturer of Rebirth research at Master Jane School of London, uk, informed me. "All maps are always very subjective.... Even the present on the internet geospatial programs on all your cellular phones and pills, be they designed by Search engines or Apple company or whoever, are still at some stage very subjective maps."

There are, in other terms, no ideal maps—just maps that (more-or-less) completely catch our knowing around the world at unique minutes soon enough. In his new guide, A Record of the World in 12 Charts, Brotton well online catalogs the maps that tell us most about critical times in the past. I requested him simply to move me through the 12 maps he chosen (you can simply simply click each map below to expand it).

1. Cartography's Foundation: Ptolemy's Location (150 AD)

Humans have been drawing maps for thousands of years, but Claudius Ptolemy was the first to use mathematical and geometry to make a guide for how to map the globe using a rectangular shape and intersecting lines—one that resurfaced in 13th-century Byzantium and was used until the early Seventeenth millennium. The Alexandria-based Ancient pupil, who may never have attracted a map himself, described the permission and longitude of more than 8,000 locations in European nations, Asia, and African-american, predicting a north-oriented, Mediterranean-focused world that was losing the The nation's, Australasia, the southern part of African-american (you can see African-american cloths the end of the map and then mixing into Asia), the Far Eastern, the Hawaiian Sea, and most of the Ocean Sea. Ptolemy's Location was a "book with a 1,500-year heritage," Brotton says.

2. Social Exchange: Al-Idrisi's World Map (1154)

Al-Sharif al-Idrisi, a Islamic from Al-Andalus, visited to Sicily to perform for the Grettle Master Mark II, generating an Arabic-language geography information that attracted on Judaism, Ancient, Spiritual, and Islamic customs and involved two world maps: the small, round one above, and 70 local maps that could be padded together. Compared with east-oriented Spiritual world maps at time, al-Idrisi's map locations the southern part of at top in the custom of Islamic mapmakers, who regarded Paradise due the southern part of (Africa is the crescent-shaped where you live now at top, and the Arabian Peninsula is in the center). Compared with Ptolemy, al-Idrisi portrayed a circumnavigable Africa—blue sea encompasses the world. Eventually, the map is involved with comprising physical geography and mixing traditions—not arithmetic or trust. "There are no creatures on his maps," Brotton says.

3. Spiritual Faith: Hereford's Mappa Mundi (1300)

This map from England's Hereford Church symbolizes "what the world seemed like to ancient Christian believers," Brotton says. The planning concept in the east-oriented map 's time, not space, and particularly spiritual time; with Jesus emerging over the world, the audience moves emotionally from the Lawn of Eden at top down to the Support beams of Hercules near the Strait of Gibralter at platform (for a more specific trip, examine out this useful information to the map's landmarks). At the center is Jerusalem, noticeable with a crucifix, and to the right is African-american, whose shore is noticeable with repulsive creatures in the edges. "Once you get to the edges of what you know, those are risky locations," Brotton describes.

4. Imperial Politics: Kwon Kun's Kangnido Map (1402)

What's most stunning about this Japanese map, developed by a group of elegant astronomers led by Kwon Kun, is that north is at top. "It's unusual because the first map that looks identifiable to us as a European map is a map from South korea in 1402," Brotton notices. He chalks this up to power state policies in the area at time. "In South Oriental and China imperial philosophy, you look up northwards in regard to the emperor, and the emperor looks the southern part of to his topics," Brotton describes. European nations is a "tiny, savage speck" in the higher remaining, with a circumnavigable African-american below (it's uncertain whether the black covering in the center of African-american symbolizes a pond or a desert). The Arabian Peninsula is to Africa's right, and Indian is hardly noticeable. China suppliers is the enormous blob at the center of the map, with South korea, looking disproportionately large, to its right and the isle of Asia in the end right.

5. Territorial Exploration: Waldseemuller's Universalis Cosmographia (1507)

This perform by the In german cartographer Martin Waldseemuller is regarded the most expensive map on the world because, as Brotton notices, it is "America's beginning certificate"—a difference that persuaded the Collection of The legislature to buy it from a In german elegant prince for $10 thousand. It is the first map to identify the Hawaiian Sea and the individual area of "America," which Waldseemuller known as in regard of the then-still-living Amerigo Vespucci, who recognized the The nation's as a unique where you live now (Vespucci and Ptolemy appear at the top of the map). The map includes 12 woodcuts and features many of the newest findings by European adventurers (you get the sense that the woodcutter was requested at the last moment to make room for the Cpe of Good Hope). "This is when when the world goes hit, and all these findings are made over a few months frame," Brotton says.

6. Politicized Geography: Ribeiro's World Map (1529)

The Colonial cartographer Diogo Ribeiro consisting this map amongst a nasty argument between Italy and This particular terminology over the Moluccas, an isle sequence in present-day Philippines and hub for the liven business (in 1494, the two nations had finalized a agreement splitting the recently found areas in two). After Ferdinand Magellan's adventure circumnavigated the world for initially in 1522, Ribeiro, operating for the Spanish terminology top, placed the "Spice Isles," inaccurately, just inside the Spanish terminology half of his apparently medical world maps. Ribeiro may have known that hawaii (which appear on the far-left and far-right factors of the map) actually belonged to This particular terminology, but he also realized who compensated the expenses. "This is the first great example of state policies adjusting geography," Brotton says.

7. Territorial Navigation: Mercator's World Map (1569)

Next to Ptolemy, Brotton says, Gerardus Mercator is the most significant determine in the reputation of mapmaking. The Flemish-German cartographer tried "on a smooth piece of document to imitate the curve of the planet's surface area," allowing "him to attract a directly range from, say, Lisbon to the European Coast of the Declares and sustain an effective range of keeping." Mercator, who was locked up by Catholic regulators for claimed Lutheran heresy, developed his map for European navigators. But Brotton believes it had a higher objective as well. "I think it’s a map about stoicism and transcendence," he says. "If you look at the world from several countless numbers kilometers up, at all these disputes in religious and governmental life, you are like bugs operating around." Mercator has been charged of Eurocentrism, since his projector screen, which is still sometimes used these days, progressively alters area as you go further the southern part of and north from the equator. Brotton dismisses this view, disagreeing that European nations isn't even at the center of the map.

8. Commercial Cartography: Blaeu's Atlas maior (1662)

Working for the Nederlander Eastern Indian Company, Joan Blaeu designed a wide atlas with thousands of baroque maps occupying a large number of webpages. "He's the last of a tradition: the single, amazing, magician-like mapmaker who says, 'I can amazingly show you the whole world,'" Brotton says. "By the delayed Seventeenth millennium, with combined stock organizations applying every area around the world, unknown groups of people are bashing information and generating maps." Blaeu's market-oriented maps weren't cutting-edge. But he did break with a mapmaking custom way returning to Ptolemy of putting the world at the center of the galaxy. At the top of the map, the sun is at the center of personifications of the five known planet's at the time—in a nod to Copernicus's concept of the galaxy, even as the world, separated into two hemispheres, continues to be at the center of the map, in deference to Ptolemy (Ptolemy is in the higher remaining, and Copernicus in the higher right). "Blau silently, very carefully says I think Copernicus is probably right," Brotton says.

9. Nationwide Mapping: Cassini's Map of Italy (1744)

Beginning under Louis XIV, four years of the Cassini family presided over the first make an effort to study and map every gauge of a country. The Cassinis used the technology of triangulation to make this nearly 200-sheet topographic map, which France revolutionaries nationalized in the delayed 1700s. This, Brotton says, "is the beginning of what we understand as contemporary nation-state applying ... whereas, before, mapmaking was in personal arms. Now, in the Search engines era, mapmaking is again going into personal arms."

10. Geopolitics: Mackinder's 'Geographical Rotate of History' (1904)

Don't let the modesty of this "little range drawing" deceive you, Brotton says: It "basically designed the whole idea that state policies is motivated at some stage by geographical problems." The British geographer and imperialist Halford Mackinder involved the illustrating in a document disagreeing that Russian federation and Main Asia constituted "the pivot of the state policies." Brotton considers this idea—that control of certain critical areas can convert into worldwide hegemony—has affected numbers which range from the Nazis to Henry Orwell to Gretchen Kissinger.

11. Geoactivism: Peters's Projection (1973)

In 1973, the left-wing In german historian Arno Peters revealed an substitute to Mercator's supposedly Eurocentric projection: a world map illustrating nations and major areas according to their actual surface area area—hence the smaller-than-expected north major areas, and African-american and South The america showing, in Brotton's terms, "like long, swollen split falls." The 'equal area' projector screen, which was nearly similar to an previously design by the Scottish clergyman Wayne Gall, was a hit with the media and contemporary NGOs. But experts suggested that any projector screen of a rounded surface area onto a aircraft surface area includes disturbances, and that Peters had elevated these by choosing serious statistical mistakes. "No map is any better or more intense than any other map," Brotton says. "It's just about what plan it chases."

The European Side enshrined the Peters Projection in popular lifestyle during an show in which the fake Organization of Cartographers for Social Equivalent rights lobbies the White House to make it compulsory for community educational institutions to educate Peters's map rather than Mercator's.

12. Exclusive Mapping: Search engines World (2005)

Google is at the leading advantage of enhancements in digital mapmaking, Brotton says. But he also notices that the company recognizes maps as an adjunct to search and marketing. "My query is what gets on maps, who will pay to get on maps now, and who can't pay and is therefore not on maps?" he requests. Long ago in Mercator's day, resource rule contains the projector screen the cartographer used and the information he fed into it. Now, Brotton notices, we don't know what resource rule Search engines and other on the internet applying programs are using. And this at some point when Search engines, which provides customers more than 20 petabytes of visuals, is dealing with far more content than a country can coordinate. "Companies can now generate maps in more details than, say, the U.K. Ordnance Survey, but without any peer-observation process," Brotton claims.

No comments:

Post a Comment